In this episode of the Missio Savannah Podcast, a recent SCAD graduate shares his testimony about grassroots discipleship and life as international student.

Fourth Friday Artist Retreat

There is a new monthly rhythm happening at Wesley Gardens!

Following our usual Fourth Friday retreat, lunch will be offered & then Allison Hall will guide a retreat for creatives—no cost and all are welcome.

Here’s the pattern . . .

8:45am: Coffee/tea at the gazebo

9am-12:30pm: Morning prayer retreat (gently guided & no experience needed)

12:45pm: Lunch at the pavilion by @twojacketjulie 💛

1:30pm: Artist retreat begins

3pm: “Structured time” ends, but you’re welcome to linger and continue creating on your own

Drew Ibach is Here!

Drew Ibach is a new arrival to Savannah. Drew is a recent graduate of Duke Divinity School who is serving as curate at Christ Church Anglican.

In this episode of the Missio Savannah podcast, Drew talks a bit about his own story, his new role in Savannah, and an initiative to host monthly installations by local artists at the corner of Bull and 37th Street.

Lillis Weeks: Life's a Quilt, A Testimony of Mission, Music and Mentorship

In this episode of the Missio Savannah Podcast Lillis Weeks Lillis shares a testimony of service and cross cultural experiences as she makes her way from the DRC to the Ivory Coast, from Duke to Morocco and London, from Nairobi to Johannesburg, and on the her current mission as music teacher at the Habersham School.

Lillis also discusses her appreciation of quilting as both a form of art and a means of community.

Rick Monroe Talks about a Life of Youth Ministry in Savannah

Rick Monroe has been a leader in youth ministry for over 50 years!

In this episode of the Missio Savannah Podcast Rick shares about his call to the task of youth evangelism through Young Life and some of what he has learned along the way.

Lisa McCaslin: How to Care for Vulnerable Children in Our Community through Promise 686

Lisa McCaslin is the Area Director at Promise686 for Southeast Georgia.

Through her role with Promise 686, Lisa mobilizes local churches and christians to care for vulnerable children through the generous and loving support of families and foster care givers.

In this episode of the Missio Savannah podcast Lisa shares about Promise 686's mission is to fulfill God's promise "to set the lonely in families."

Scoggins Berg: Jesus, Bono and the ONE Campaign

Scoggins Berg is the U.S. Senior Regional Organizing Manager & Faith Lead at The ONE Campaign.

In this episode of the Missio Savannah Podcast Scoggins shares about how he got involved with the One Campaign and the global work that he does from his couch in Savannah, Georgia.

"Child of the Plantation" by Drew Miller

Oak Tree, by Helen Kapp

My family owns several hundred acres on an island outside of Charleston, and we have owned them since the 1820s. In recent decades we grew trees on the land. I grew up with them, those loblolly and long-leaf pines planted in straight lines on either side of the state road. Viewed across the rows, the trees looked like any Lowcountry forest, dark, irregular and impenetrable. Viewed down the rows, the trees made perfect parallel paths into the distance, heavy with evergreen shadows, drawing us with unnatural gravity into the dark unfathomable distance, opening a path onto the hidden, unknowable things of a southern plantation.

A storm took the crop several years ago, snapping the trees like so many pencils stood in the ground. We didn’t see it coming. We didn’t have insurance. We sold the scraps for mulch, made enough to cut and burn and plant again. Another round dealt in hope; farming is always a gamble against the times. The new trees now stand chest-high, struggling against vine and bramble in their adolescence. Soon they will tower above the brush and shade out their weaker-kneed competition, but for now their diminished height leaves our land curiously exposed. The house, the river, the family graveyard. Even the servant graveyard is more exposed, though still hidden from the road. It stands overgrown in a corner of the fields.

The servant graveyard is made up of several dozen graves, most unmarked and recognizable only by the slight depression of collapsed pine coffins. Black house servants and field hands and their slave forebears could rarely afford to commemorate the lives of their loved ones with any permanence. A few graves have metal markers, a couple have marble headstones. One particularly small depression has a low brick wall around it, no more than two feet by four feet, and is covered in brambles, collapsing.

As children we avoided the graveyard unless we were telling ghost stories by lamplight. There was a story about the island I once heard and often retold, about a servant boy who ran off with the daughter of a plantation owner. The father chased them down on horseback, and when their carriage overturned on the twisted roots of an ancient live oak the father and his brothers hung the young man on its heavy branches. Whenever I told the story I’d point to the biggest oak within sight, nod, and say, “There--that one.” My grim silence always proved convincing, sometimes even to myself. After all, I could never be sure it hadn’t been on that tree, or on the next.

We built forts in the pine forest, and cut trails through the rows to connect our outposts. We followed deer and rabbit paths, shallow indentations in the needles like channels for our feet. In the winter we whittled cane spears and improvised muskets, raiding Indian camps and pirate ships until it grew dark and the old cast iron bell called us home. My cousin and I lived on opposite ends of the property, divided by seven houses of relatives. At the sounding of the bell we would stash our weapons and part ways, he to the Northwest, and I the Southeast, to our respective homes and dinners and anxious mothers. On special occasions we would camp in the forest, building small fires to ward off the darkness. We camped just south of the servant graveyard, east from the pits that were likely dug by slaves to process Carolina indigo.

My family arrived as second-wave immigrants to Charlestowne just before the War of Independence, French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution and seeking a better life. We found one. My great-great-great-great grandfather rose quickly to prominence, rubbing shoulders with the leaders of South Carolina’s colonial period until he was sent as a delegate to the Continental Congress. He owned vast properties across the state, thousands of acres of planted crops and a few stately homes. He owned a house on Church Street downtown. And he owned people, and likely a great many. He was offered a shipment of over a thousand slaves at one time according to some preserved letters we’ve found, but apparently passed by the opportunity. And sometime around 1820 he bought our small plantation on Johns Island, a ferry or two from Charlestowne, sprawling alongside a tidal river.

By the time my grandfather acquired it, generations later, the family had lost its prominence. The War between the States, a bankruptcy, and a house fire had taken most of our belongings. My grandfather farmed the land and repaired state school busses to pay the bills. My grandmother was a school teacher and kept children of her own. They ate what they grew or caught or shot, and drank sulfurous water from the ground. Fifty years after the well was dug the Clemson extension would test the water and declare it ‘unfit for plant or animal consumption,’ though I swear, it makes the best sweet tea in the South.

When my grandfather retired from farming seasonal crops, he gave away or sold land to cousins of varying degrees and planted pines on the rest. He planted the pines by hand, one at a time, in straight rows behind an ancient pickup. He farmed trees to maintain the agricultural tax subsidy on the land and to have a little nest egg; the storm dashed that nest to pieces, so he started again. He let someone else plant this time and regrets it. Blindfolded children could have drawn straighter lines. Still the pines grow, and every month the trees bury what stands behind them, inches at a time. My house, the river, the graveyards.

My family has lived here since 1820. Few people have roots like that anymore, roots like those of tall pines that do not spread but dig deeply into one place. The taproot of a pine grows so deep that a pine will break in half before it uproots. A powerful oak will overturn, leaving upright a wall of earth and matted roots attached to its fallen trunk. A pine bends until it snaps clear away. A storm can kill such a tree, though it cannot move it.

My family knows this land. Every slope and hollow, every towering pecan, every petering ditch. The dirt roads have names tied to their all-but-forgotten past. We remember them. We’ve plowed these fields for so long that the furrows are cut into our feet, our minds, our souls. This is my home. It’s who I am. I am a child of the plantation.

And so were they. The bodies in the servant graveyard belonged to children of the plantation, too--the smaller grave from one such child that never grew, as I did, into southern adulthood. A child of the plantation lies hidden behind the forest, while I tell ghost stories about her cousins. A child of the plantation like me, and not like me at all.

I used to tell my friends that we’ve been here since 1820, and with pride. I hesitate now. I don’t know whether it was Fergusson that slowed my tongue, or Mother Emmanuel. Serving in a majority-minority congregation for a time had much to do with it, I know. By whatever cause, I hesitate. I stutter.

I am a child of the plantation. I reaped its many benefits, and I still do. I walk the fields that slaves once plowed. I don’t know if their backs were as scarred as the earth beneath them, but when we plow the fields for our gardens we still find their numbered metal tags and shards of the pottery they made for cooking and eating. I swim where slaves once loaded crops onto ships to be sold in town for my great-great-grandfather. The colonial dock posts are still visible in the ground, kept from rot by the salt and the sand and anaerobic silt. But the posts are slowly disappearing as the bank erodes, slowly erased with the stories of cruelty they witnessed. I sit at the kitchen table and watch the river drift lazily by. One hundred and fifty years ago slave quarters would have blocked my view, standing between today’s tree fort and tire swing.

I am a child of the plantation. I live on the fields of her history. I benefited from it. I still do. Other children of the plantation felt its violence, and profited not at all. Still don’t. History is not so removed from the present in the South. My grandfather knew a man who fought at Antietam.

I am a child of the plantation, and I am not sure what that means anymore. My childhood was idyllic and its glories true. To deny them would be wicked and as false as denying their despised companions. There is glory here, and also such storms as swallow forests whole. Storms which threaten to lay bear what our hearts have buried, to overturn what will not give way, to break what cannot be overturned.

Only one tree has ever withstood such a storm. On it hung a dark-skinned man and a king, strange fruit as hung on so many southern trees. The church of which I am a minister has long claimed the one and not the rest: the cross and not the live oak, grace and not repentance, forgiveness and not penance, reconciliation and not justice. We have believed that unmerited favor is not costly. We do so at our peril. For the king who suffered comes again, riding on the clouds of judgement. The storm we expect for our enemies breaks first on the household of God. It rewrites our very landscapes, our histories, our lives- whether or not we have surrendered to its coming. And no one knows the hour of this storm.

The Rev. Drew Miler serves as the Pastor of Statesboro Anglican Mission. He loves fiction, sad music, river sailing, good coffee, and trees. All the trees.

https://www.statesboroanglican.org/about

They Count Now

by Lance Levens

Mark Noll, author of “America’s God,” suggests that the foundation for the American Revolution was laid by The Great Awakening. How is it then, without communication, that an awakening occurred? Was there an underground network the history books missed? No, there was no underground network; but there was George Whitefield. Mr. Wesley helped out for a year; Mr. Whitfield stayed longer and helped establish our nation.

This tenacious preacher (1714-1770), working out of his own parish, Christ Church, Savannah, GA, delivered sermons up and down the Atlantic seaboard when there were no trains, cars, and no state-maintained rest stops to freshen up at. George Whitefield, Oxford-educated Englishman, freshened up in the creeks of the Carolinas and the ponds of Georgia and Virginia and Massachusetts, and the rivers, the Chickahominy, the Rappahannock and the Pedee. He made his own fire every night, sometimes from pine wood and sometimes poplar and sometimes birch. At one point he rode on horseback from New York to Charleston, preaching along the way, holding out his hat, as always, to collect money for his heart’s project in Savannah: The Bethesda Children’s Home, an institution that is still in operation today. Although Merriam-Webster’s lexicographers would never permit it, the word “itinerant” should stand in their dictionary under a separate listing, as an homage to George Whitefield.

But the sad truth is: you won’t find a great deal about George Whitefield anywhere, least of all in the school room history books. You would think any eighteenth century historian of American culture would be enthusiastic about a man who appears to have played a formative role preparing the American colonists spiritually to draw a line in the sand and go to war to defend their freedom, a man who brought colonists the real ammunition they required. In all likelihood the hard-nosed traits the colonists had to cultivate to survive became an obstacle to confessing sin, forgiving sinners and forgiving self, to accepting the balm of God’s love and walking with him, daily. When a man is constantly on his guard against some outside elements that threaten him physically, psychically or emotionally, he often puts up barriers to protect himself. Whitefield’s task, as he most likely saw it, was to break down those barriers and open the hearts of men and women throughout the colonies to the love of God in Christ.

Why, then, has he suffered the abuse of omission from our national narrative? Listen to Publisher’s Weekly review of the Harry Stout-Mark Noll volume: The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism.

“…the key to Whitefield's success on both sides of the Atlantic is to be found in his theatricality. He quickly recognized the power of open-air field preaching. He was a shameless, egotistical self-promoter who, in a startling parallel with modern televangelists, consciously (albeit sincerely) employed histrionics with all the dramatic artifice of a huckster, a traveling salesman for the New Birth. By the end, according to Stout, there was no private person, only the public preacher…”

Listen to the condescension. Whitfield is condemned because he merely understood the rules of rhetoric. Cicero, Demosthenes: both gesticulated, both performed—and both are praised for doing so. Pre-microphone speakers had to do that. But Whitefield is to be held to a higher, NPR standard? Tight-tongued, tight-lipped? Is he to be chastised for simply knowing the orator’s craft?

Or is he chastised because he espoused an orthodox Christianity that the early fathers such as Augustine and Athanasius would have applauded?

What does it mean to be a founder? What is our foundation? Many would point to the Constitution, The Declaration, The Bill of Rights. I would simply pose this question: why should I count at all? Why do I deserve life and liberty at all?

Perhaps Flannery O’Connor gives us an answer in her short story “The River.” The protagonist is Bevel, a ten year old boy who is about to be baptized by an unnamed preacher in an unnamed river somewhere in South Georgia:

“Suddenly the preacher said: ‘All right, I’m going to baptize you now.’ And without more warning, he tightened his hold and swung him upside down and plunged his head into the water. He held him under while he said the words of baptism and then he jerked him up again and looked sternly at the gasping child. Bevel’s eyes were dark and dilated. ‘You count now,’ the preacher said. ‘You didn’t even count before.’”

They count now. That was Whitefield’s purpose, a founder’s purpose. They didn’t even count before. Whitfield wanted to ensure that his fellow colonists knew that they counted. They counted enough to believe even the most outlandish of eighteenth century claims, that they deserved life and liberty. This was our first foundation and George Whitefield was its founder.

Lance Levens is a Savanah writer and teacher.

Whitefield Preaching, Circa 19th Century (Available @ fineartamerica.com)

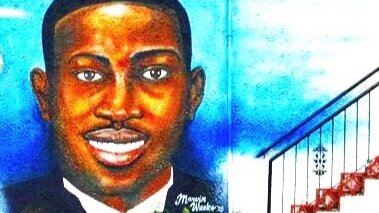

Open Letter to Travis McMichael

Dear Travis,

Even more than the rest of us from Brunswick, I am sure you remember Ahmaud’s name every day. You and the others involved in his death made Ahmaud and Brunswick famous for injustice. You are not the only ones responsible. I am partly to blame. Many others from Brunswick are partly to blame. Instinctively, you chased Ahmaud down. Instinctively, you shot Ahmaud until he stopped moving. We are part of the community that allowed those instincts to grow in a culture of ignorance and fear. We need to be humble, listen, learn, and work to right our wrongs. You can help us. You can still do something thoughtful and brave.

When I saw the video of Ahmaud running through your neighborhood, I thought about points. Before I moved to Brunswick, I’d never heard of those points—the points you get for hitting black people with your car. Different point values for different scenarios—how many, how old, male or female, on bikes or walking. I heard about points in multiple cars with different people. At first, I was shocked. I was new in town from Kansas and afraid to ask questions. But I soon realized none of the talk was serious—no drivers actually tried to hit pedestrians. It was just another feature of Brunswick I’d need to adjust to—the smell and taste of tap water, the smell of the mill, gnats, gunfire at FLETC, banter about hypothetical racially motivated vehicular homicide.

Like you and many others, I spent my teenage years in Brunswick trying to figure out how to survive where I was and find my slice of the American dream. Most of us lived at home, went to school, and went to church. We all grew up like the Georgia pines surrounding us—in the same light and weather, pushing tap roots deep into Brunswick culture. Everything that grew was allowed to keep growing just as it had been growing for longer than anyone tried to remember.

This is not just a Brunswick problem. I’ve lived in many places in different countries. I’ve met thousands of kind and thoughtful people, but only know a handful who were raised in homes where they were taught—with the same degree of repetition and rigor required to learn complicated math or a second language—that every human being is worthy of being treated with respect and dignity. Many of us have memorized some of the words of The Declaration of Independence, but we haven’t let them sink any deeper into our experience than other facts we’ve been required to remember to pass tests. Most of us have not been taught that dehumanizing “the other” is wrong, allowing someone else to dehumanize “the other” is also wrong, and both lead to catastrophic consequences.

We learned in Brunswick schools—in the classroom, on the bus, in the halls, during PE, in the locker room, at lunch. There wasn’t significant racial tension, but there was separation. There was a white way and a black way to do things—walk, talk, dress, dance, laugh. You were expected to learn and maintain your way. Like most students, when teachers weren’t around, we pursued our social needs enjoying jokes and stories. They weren’t all mean-spirited, but most of them raised the beautiful strong over the misfit weak—the poor, the awkward, the disabled, “the other.” Sometimes “the other” was black people, but not often. The problem wasn’t racists stories or jokes. The problem was that we were continually entertained by the recycling of dehumanizing narratives and no one protested. No one confronted, challenged, told on, or even winced or rolled their eyes when the jokes and stories were told. We were either afraid of the consequences of doing the right thing or too desensitized to know anything was wrong.

Most of the people I knew in Brunswick were in church every Sunday—including the kids and fathers who talked about points in the car. In the church where my family settled, among good friends and good people, we were told things that would help us get to Heaven and help us tell others how to get to Heaven. Sunday mornings began in Sunday School and ended on the front steps of the church, but none of us could walk out the front doors to whatever Sunday afternoon promised until we had passed through the filter of an altar call—an invitation to walk the aisle to pray with the preacher to get right with God.

The hymn was usually “Just as I Am,” reminding us that God is always inviting us to come to him immediately—dirty, broken, in sin—before it’s too late. Some Sundays, my heart would beat faster, my palms would sweat, and I’d recognize the urgency and fear. I was too ashamed to walk the aisle, but I’d pray and confess the sins I connected to the guilt—the things I knew were wrong because my leaders spent time and energy convincing and reminding me that those things were wrong. I confessed and walked out into Sunday afternoon, cleansed by the blood of the Lamb, ready for Heaven.

But I never confessed anything connected to the times I said the N-word, the racist jokes I laughed at and repeated, the racist chants I memorized and joined in, the times I chuckled in the back seat when people talked about points. I didn’t think of those things as dangerous to anyone. I was never told that racism is a sin and not challenging racism is a sin. I should have been told those things—directly, repeatedly. I doubt you were told those things. I’m sorry, Travis. I’m part of the community that let you down. The people of Brunswick share responsibility for what you were told, what you experienced—for not adequately teaching you the value of every human life. That collective failure led to you and your father in a truck in the street with guns pointed at Ahmaud. It led to you killing Ahmaud and cursing his dead body in the street.

Unlike Georgia pines, we have the capacity to reason—to love, hate, fight, protect, confess, forgive. There is much to love and hate, to fight against and protect from, but there is more to confess and forgive. Travis, please forgive me—forgive your community.

I’m sorry, Travis. We let you down. We must accept our guilt and the guilt of our parents, and leaders. We must work to make it right. You can help us. You are responsible for all your thoughts and actions. Pray for the courage to see clearly, to own your actions and the consequences, to speak clearly, and honestly.

Give Ahmaud’s family a reason to think about forgiving you. Millions of people hate you for being another white man who killed an unarmed black man. Give those people a reason to see the humanity in you—the humanity we fail to see in our enemies—the humanity you failed to see in Ahmaud. Travis, lead us. Show us how to humble ourselves, as the hymn says, in the midst of our conflict, doubts, fighting, and fear, just as we are, wretched in sin, blind in ignorance. May we all follow. May we all repent by seeking healing of the mind.

Be brave. Regret what you did. Look at Ahmaud’s family.

No one can stop you from speaking the truth. No one can stop you from pleading guilty.

Jason Mehl

Source Image: Mural in Brunswick, Georgia by Marvin Weeks

Virtual Sunday School as Art

These virtual Sunday school videos featuring local minister Rev. Joe Gasbarre and produced by Brian Flood are well worth the bandwidth:

Job: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v1OLbRhmZgs&feature=youtu.be

Abraham: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUR-1grDCbM&feature=youtu.be

"George Floyd and Me" by Shai Linne

Click the link below to read an important message from Shai Linne posted on the Gospel Coalition’s website. His perspective is worth reading.

https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/george-floyd-and-me/

How then should we live in light of the lived experiences recounted by Shai?

Living Creatures Podcast: Savannah Artists to the Helpscue!

In this edition of the Living Creatures Podcast, Braelyn Snow shares about how Savannah artists who can sew are meeting critical health needs in response to the COVID-19 epidemic.

Living Creatures Podcast: Savannah Artists to the Helpscue!

https://www.buzzsprout.com/264559/3219397

Go to https://www.gofundme.com/f/kmkds4-masks-for-savannah-medical-workers to help support this initiative.

To learn more about Abode visit their website at https://abodesavannah.com/pages/about-abode

David Taylor on the Intersection Podcast

In latest edition of the Intersection Podcast, David O. Taylor of Fuller Seminary talks about how the Church can respond missionally in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic, how our worship can stay embodied even when we’re meeting online, and the long-term impact the pandemic might have on the Church.

https://www.teloscollective.com/missional-leadership-in-a-time-of-uncertainty-with-david-taylor/

The Breath & The Clay

The Breath & The Clay Conference offers a great model for engaging art, faith and culture in community:

The EveryCampus Initiative

Let’s make sure Savannah campuses are covered in prayer. Check out the Every Campus Initiative.

King in the Pulpit

Click here to learn about the King in the Pulpit initiative 2020.

Prayer

Hasten, O Father, the coming of your kingdom; and grant that we your servant, who now live by faith, may with joy behold you Son at his coming glorious majesty; even Jesus Christ, our only Mediator and Advocate. Amen.