Dear Travis,

Even more than the rest of us from Brunswick, I am sure you remember Ahmaud’s name every day. You and the others involved in his death made Ahmaud and Brunswick famous for injustice. You are not the only ones responsible. I am partly to blame. Many others from Brunswick are partly to blame. Instinctively, you chased Ahmaud down. Instinctively, you shot Ahmaud until he stopped moving. We are part of the community that allowed those instincts to grow in a culture of ignorance and fear. We need to be humble, listen, learn, and work to right our wrongs. You can help us. You can still do something thoughtful and brave.

When I saw the video of Ahmaud running through your neighborhood, I thought about points. Before I moved to Brunswick, I’d never heard of those points—the points you get for hitting black people with your car. Different point values for different scenarios—how many, how old, male or female, on bikes or walking. I heard about points in multiple cars with different people. At first, I was shocked. I was new in town from Kansas and afraid to ask questions. But I soon realized none of the talk was serious—no drivers actually tried to hit pedestrians. It was just another feature of Brunswick I’d need to adjust to—the smell and taste of tap water, the smell of the mill, gnats, gunfire at FLETC, banter about hypothetical racially motivated vehicular homicide.

Like you and many others, I spent my teenage years in Brunswick trying to figure out how to survive where I was and find my slice of the American dream. Most of us lived at home, went to school, and went to church. We all grew up like the Georgia pines surrounding us—in the same light and weather, pushing tap roots deep into Brunswick culture. Everything that grew was allowed to keep growing just as it had been growing for longer than anyone tried to remember.

This is not just a Brunswick problem. I’ve lived in many places in different countries. I’ve met thousands of kind and thoughtful people, but only know a handful who were raised in homes where they were taught—with the same degree of repetition and rigor required to learn complicated math or a second language—that every human being is worthy of being treated with respect and dignity. Many of us have memorized some of the words of The Declaration of Independence, but we haven’t let them sink any deeper into our experience than other facts we’ve been required to remember to pass tests. Most of us have not been taught that dehumanizing “the other” is wrong, allowing someone else to dehumanize “the other” is also wrong, and both lead to catastrophic consequences.

We learned in Brunswick schools—in the classroom, on the bus, in the halls, during PE, in the locker room, at lunch. There wasn’t significant racial tension, but there was separation. There was a white way and a black way to do things—walk, talk, dress, dance, laugh. You were expected to learn and maintain your way. Like most students, when teachers weren’t around, we pursued our social needs enjoying jokes and stories. They weren’t all mean-spirited, but most of them raised the beautiful strong over the misfit weak—the poor, the awkward, the disabled, “the other.” Sometimes “the other” was black people, but not often. The problem wasn’t racists stories or jokes. The problem was that we were continually entertained by the recycling of dehumanizing narratives and no one protested. No one confronted, challenged, told on, or even winced or rolled their eyes when the jokes and stories were told. We were either afraid of the consequences of doing the right thing or too desensitized to know anything was wrong.

Most of the people I knew in Brunswick were in church every Sunday—including the kids and fathers who talked about points in the car. In the church where my family settled, among good friends and good people, we were told things that would help us get to Heaven and help us tell others how to get to Heaven. Sunday mornings began in Sunday School and ended on the front steps of the church, but none of us could walk out the front doors to whatever Sunday afternoon promised until we had passed through the filter of an altar call—an invitation to walk the aisle to pray with the preacher to get right with God.

The hymn was usually “Just as I Am,” reminding us that God is always inviting us to come to him immediately—dirty, broken, in sin—before it’s too late. Some Sundays, my heart would beat faster, my palms would sweat, and I’d recognize the urgency and fear. I was too ashamed to walk the aisle, but I’d pray and confess the sins I connected to the guilt—the things I knew were wrong because my leaders spent time and energy convincing and reminding me that those things were wrong. I confessed and walked out into Sunday afternoon, cleansed by the blood of the Lamb, ready for Heaven.

But I never confessed anything connected to the times I said the N-word, the racist jokes I laughed at and repeated, the racist chants I memorized and joined in, the times I chuckled in the back seat when people talked about points. I didn’t think of those things as dangerous to anyone. I was never told that racism is a sin and not challenging racism is a sin. I should have been told those things—directly, repeatedly. I doubt you were told those things. I’m sorry, Travis. I’m part of the community that let you down. The people of Brunswick share responsibility for what you were told, what you experienced—for not adequately teaching you the value of every human life. That collective failure led to you and your father in a truck in the street with guns pointed at Ahmaud. It led to you killing Ahmaud and cursing his dead body in the street.

Unlike Georgia pines, we have the capacity to reason—to love, hate, fight, protect, confess, forgive. There is much to love and hate, to fight against and protect from, but there is more to confess and forgive. Travis, please forgive me—forgive your community.

I’m sorry, Travis. We let you down. We must accept our guilt and the guilt of our parents, and leaders. We must work to make it right. You can help us. You are responsible for all your thoughts and actions. Pray for the courage to see clearly, to own your actions and the consequences, to speak clearly, and honestly.

Give Ahmaud’s family a reason to think about forgiving you. Millions of people hate you for being another white man who killed an unarmed black man. Give those people a reason to see the humanity in you—the humanity we fail to see in our enemies—the humanity you failed to see in Ahmaud. Travis, lead us. Show us how to humble ourselves, as the hymn says, in the midst of our conflict, doubts, fighting, and fear, just as we are, wretched in sin, blind in ignorance. May we all follow. May we all repent by seeking healing of the mind.

Be brave. Regret what you did. Look at Ahmaud’s family.

No one can stop you from speaking the truth. No one can stop you from pleading guilty.

Jason Mehl

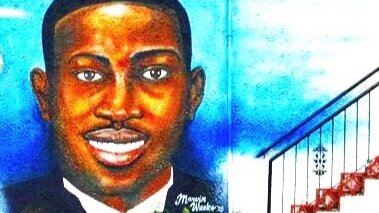

Source Image: Mural in Brunswick, Georgia by Marvin Weeks